Often bleeding disorders are inherited, meaning the disorder is passed from parents to their children. Although some people may have acquired bleeding disorders or have a spontaneous genetic mutation, many people have inherited bleeding disorders. Inheritance and genetics can seem complex, but it is important to understand how a person can get a bleeding disorder.

The genetics of bleeding disorders involve chromosomes, which are the structures where genes are located. Genes are the instructions that tell your body how to make the proteins needed for blood clotting. If there is a problem with a specific gene that affects a protein needed for blood clotting, then a person may have a bleeding disorder.

This section about how does a person get a bleeding disorder covers the following:

How Does a Person Get Hemophilia?

How Does a Person Get von Willebrand Disease?

How Does a Person Get a Rare Factor Deficiency?

How Does a Person Get a Rare Platelet Disorder?

How Does a Person Get Hemophilia?

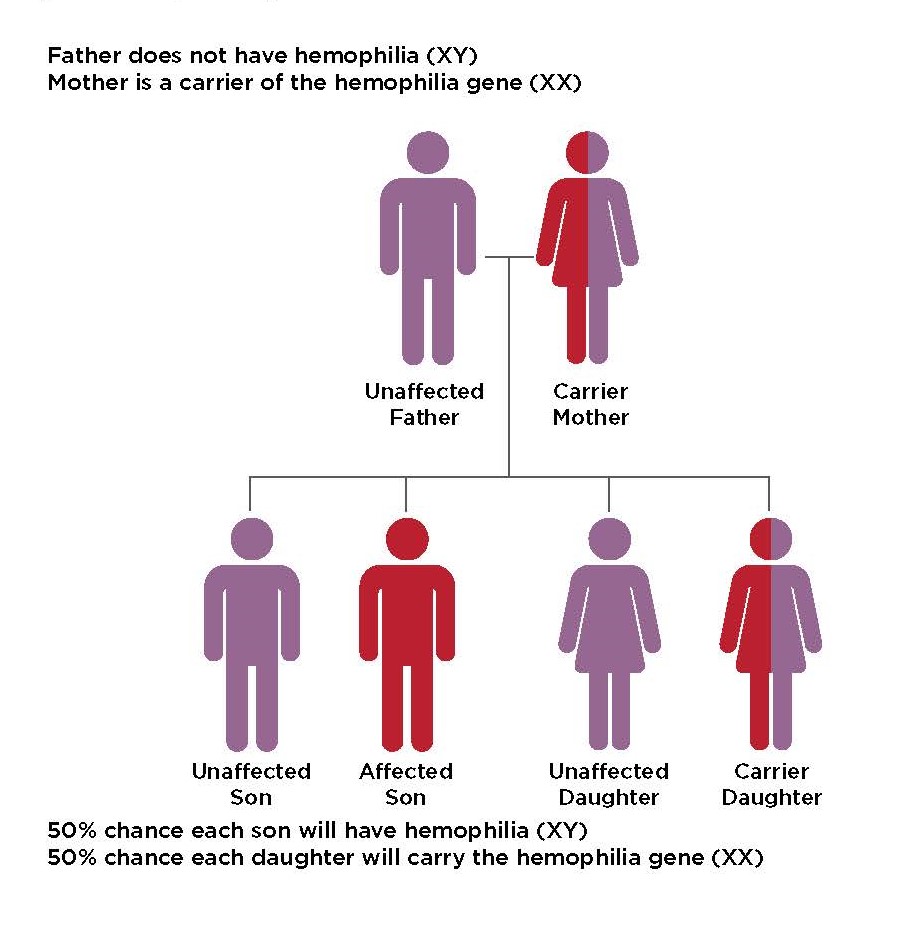

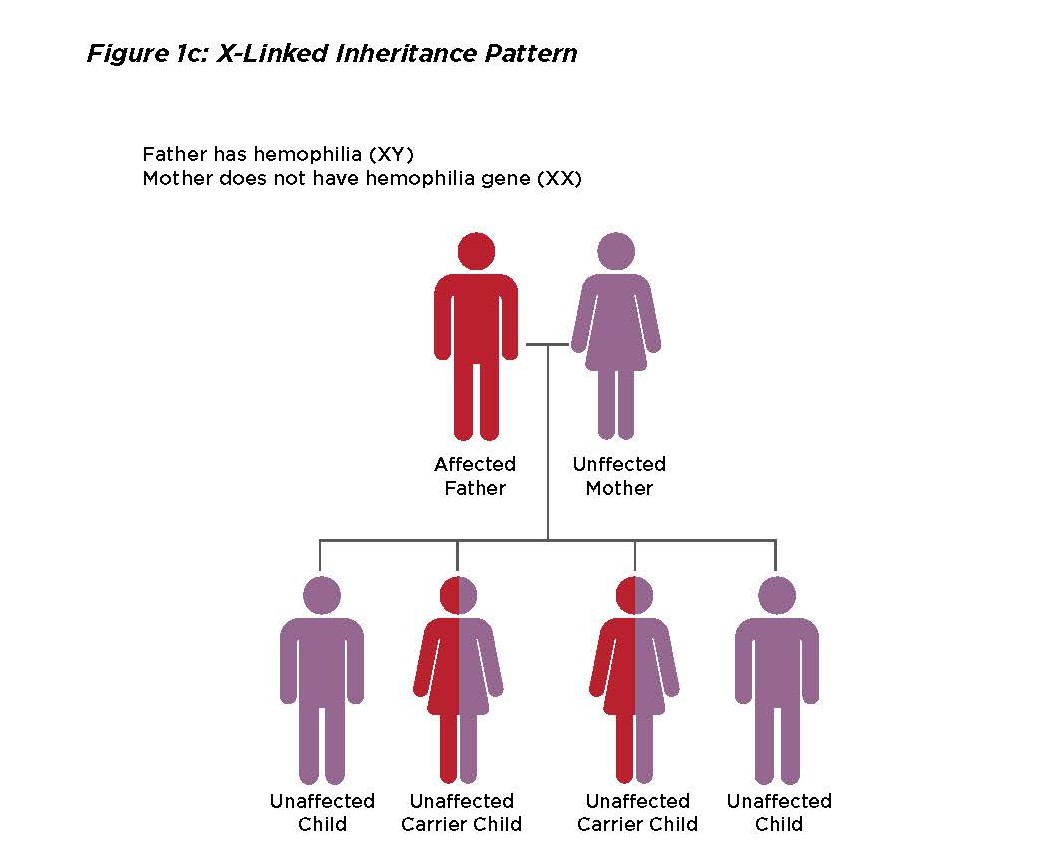

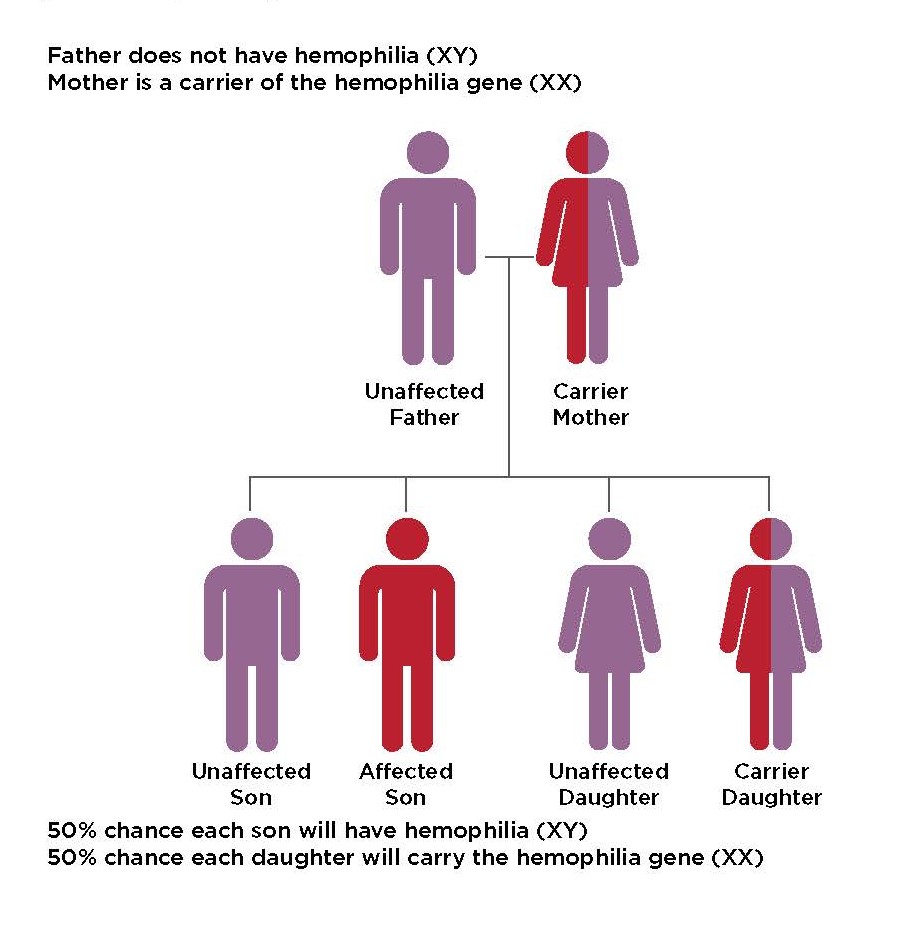

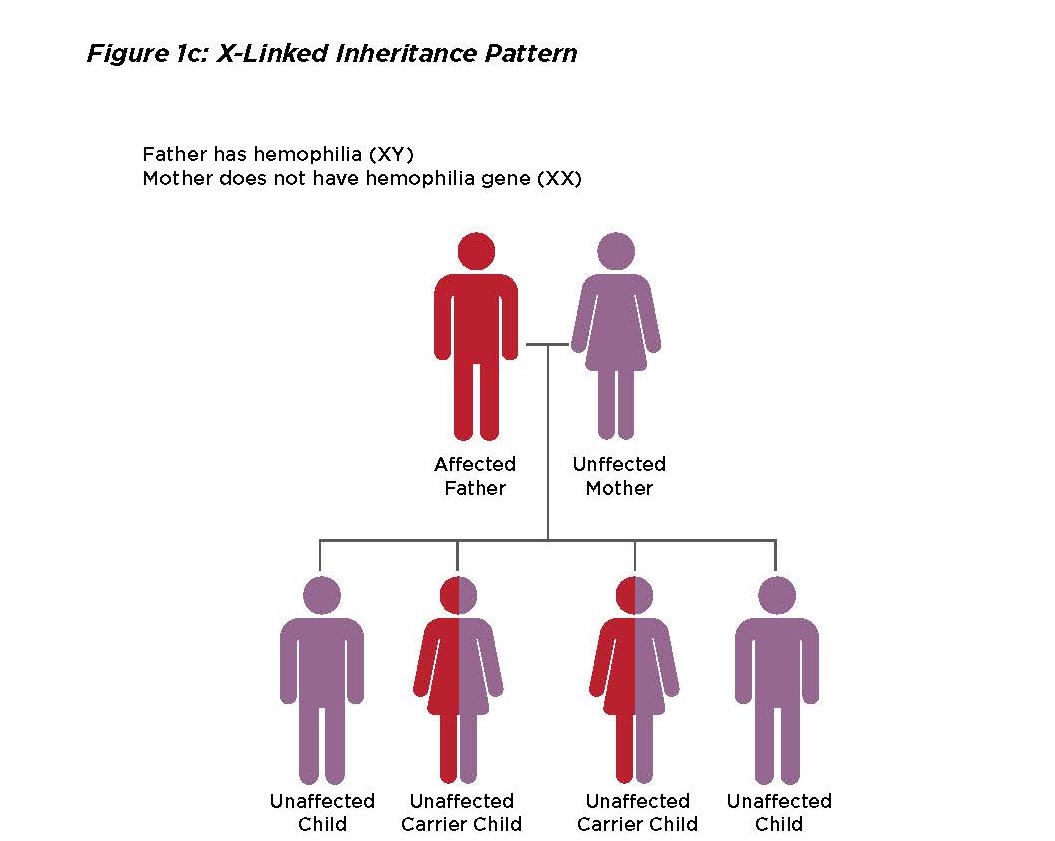

Hemophilia affects people from all racial and ethnic groups. It is caused by a problem in one of your genes. Genes tell the body to make the clotting factor proteins needed to form a blood clot. The gene for hemophilia is carried on the X chromosome. Males assigned at birth have one X and one Y chromosome (XY). Females assigned at birth have two X chromosomes (XX).

Because males assigned at birth only have one X chromosome, if they receive an X chromosome that has the affected gene, then they have hemophilia. Females assigned at birth have two X chromosomes and experience varying degrees of bleeding symptoms. If bleeding symptoms are present, then females assigned at birth may have hemophilia. If no bleeding symptoms are present, then females assigned at birth are said to be "carriers" of hemophilia. They carry the gene that causes hemophilia on the X chromosome and could pass the affected gene onto their children.

If only one X chromosome is affected, bleeding symptoms may or may not be present.

Although hemophilia is a genetic disorder, random genetic mutations sometimes occur in people who don’t have a genetic link to the condition. About one-third of people who are diagnosed with hemophilia have no family history of it.

There are two types of hemophilia including hemophilia A and B. Hemophilia A is about four times more common than hemophilia B. Half of those with hemophilia A have a severe form, which means they have less than 1% of the clotting factor they need.

Below are two diagrams of an X-linked recessive inheritance pattern:

If you want more information about hemophilia, please go to Hemophilia.

How Does a Person Get von Willebrand Disease?

VWD is a genetic disorder that is inherited, or passed down, from parent to child. VWD is an autosomal chromosome disorder, not an X-linked chromosome disorder like hemophilia. VWD affects men and women equally, so a child can inherit VWD from either of their biological parents or both parents. If you have VWD, there is a 50% chance you will pass the gene down to your child. VWD affects people from all racial and ethnic groups.

In some cases, VWD can occur when only one parent passes down the affected gene to a child. In other cases, a child will inherit the disorder only when both parents have the gene. Even if both parents have mild symptoms or no symptoms at all, their children can still be severely affected.

There are several different types and subtypes of VWD. To get VWD types 1 and 2 (except 2N), only one parent has to have the gene and pass it down to their child. This is a dominant inheritance pattern. For type 3 and type 2N, in order to have the disorder both parents have the affected gene and pass it down to their child. This is a recessive inheritance pattern.1

Although rarer, VWD can also be acquired, meaning it is not inherited. Acquired VWD is often related to an underlying disorder like a cardiovascular disorder.

If you want more information about von Willebrand disease, please go to Von Willebrand Disease.

How Does a Person Get a Rare Factor Deficiency?

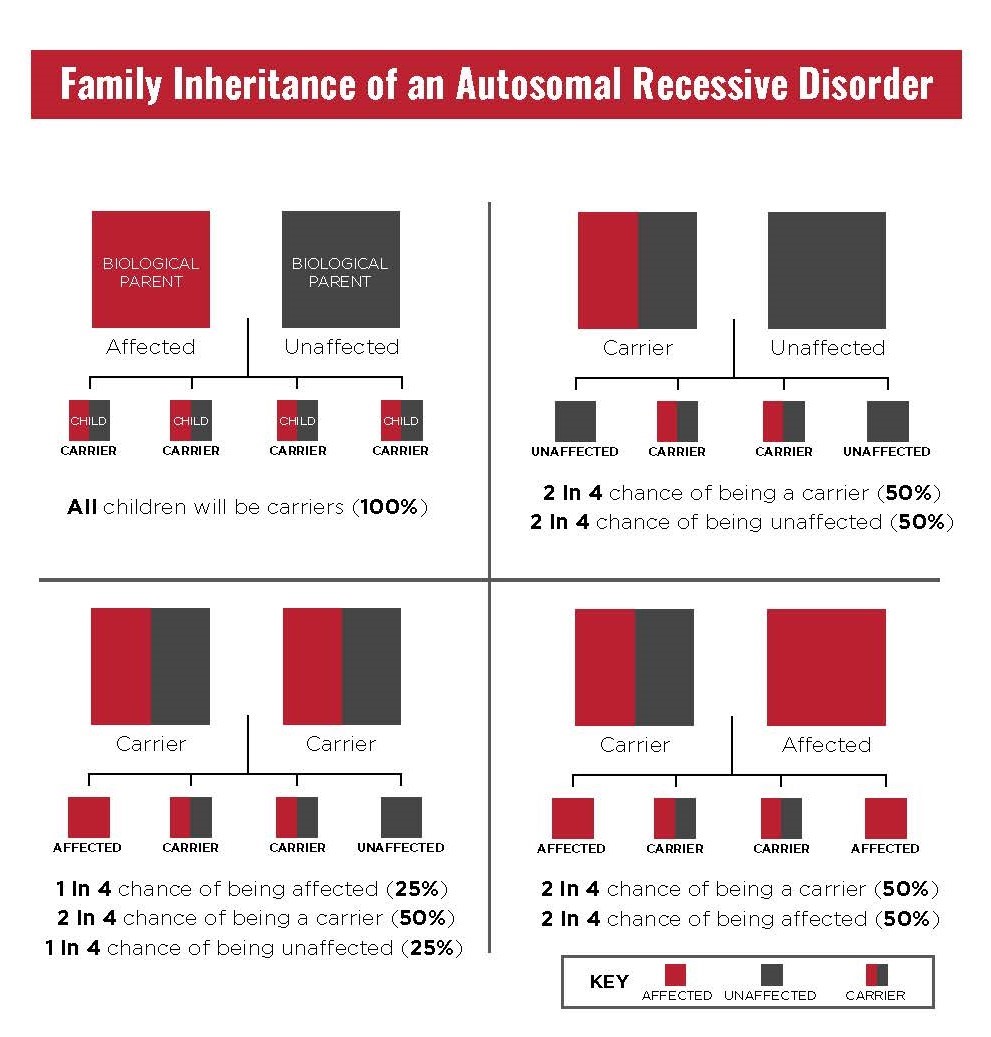

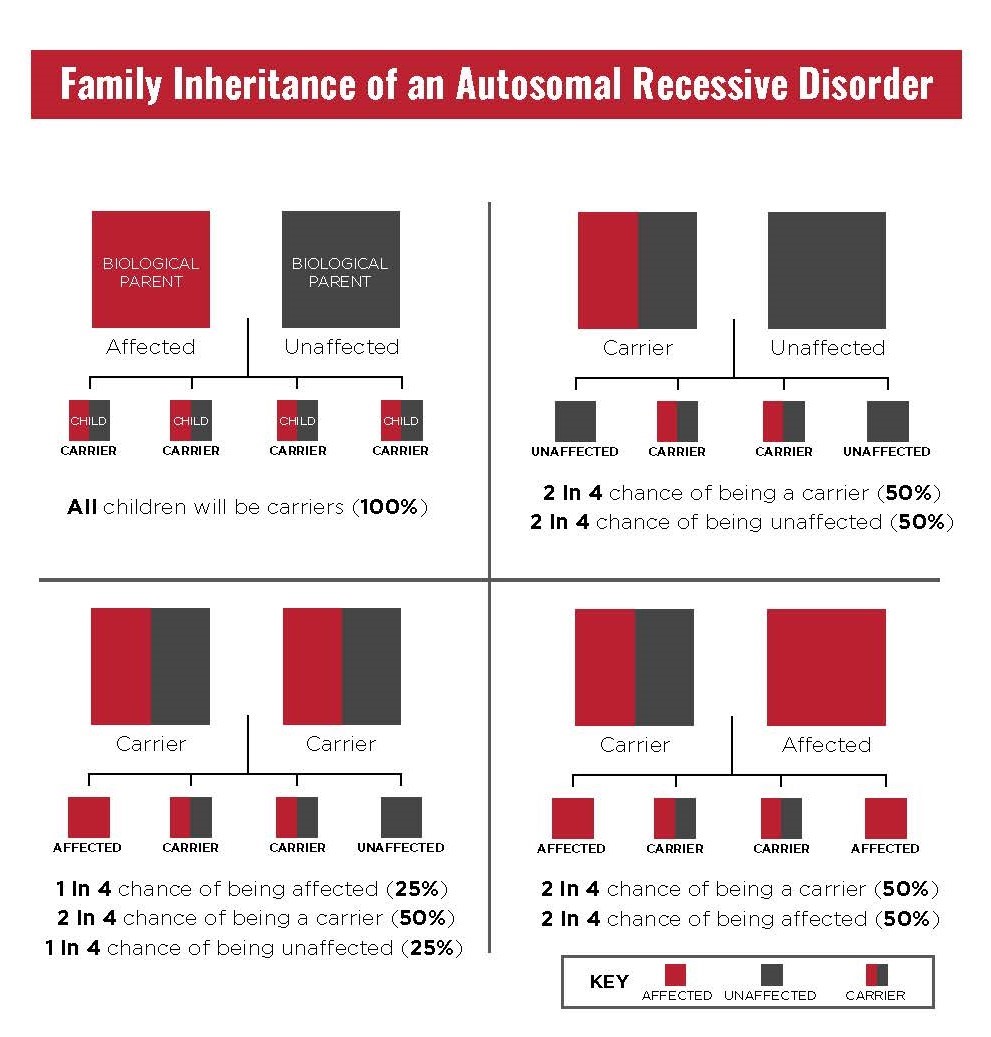

Deficiencies in the other clotting factors are not X-linked and instead the affected gene is passed down in an autosomal recessive pattern or in some cases an autosomal dominant pattern. In an autosomal recessive pattern, a child would have to receive the affected gene from both parents to have the disorder. If the child receives the affected gene from only one parent, they will be a carrier of the deficiency and may have mild symptoms. These rare clotting factor deficiencies occur equally for men and women.

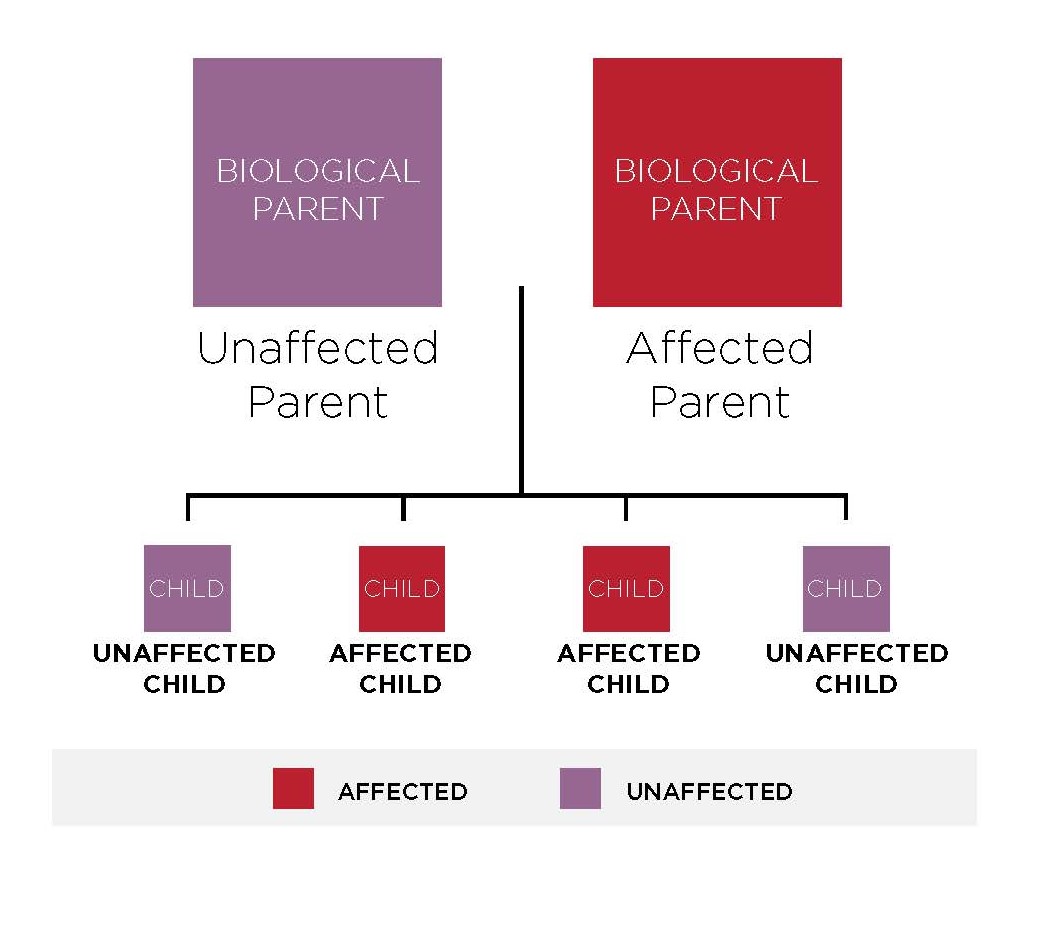

Below is a diagram of autosomal recessive inheritance pattern:

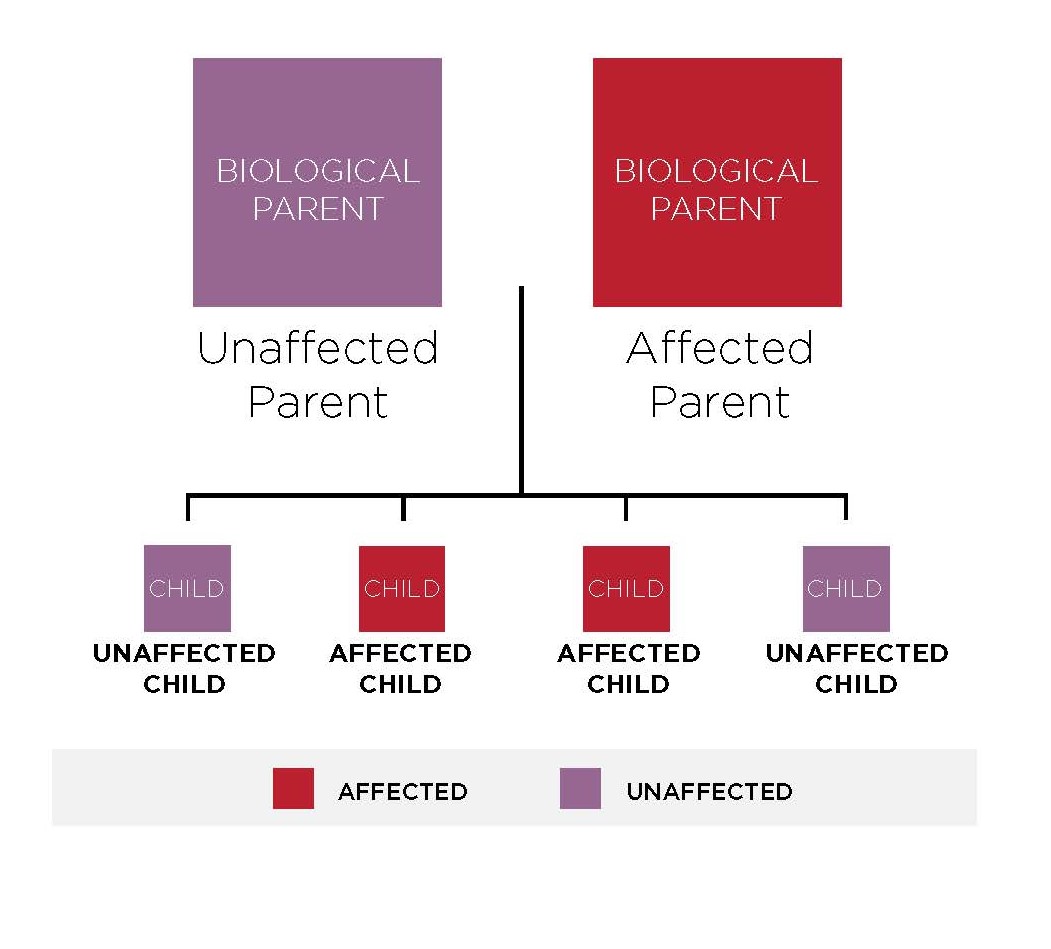

Below is a diagram of autosomal dominant inheritance pattern:

Factor I (1) deficiency is a collective term for three rare inherited fibrinogen deficiencies. These deficiencies include afibrinogenemia, hypofibrinogenemia and dysfibrinogenemia. Afibrinogenemia is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern which means both parents must carry the gene to pass it onto their child. Dysfibrinogenemia is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means that only one parent must carry the gene to pass it on to a child. Hypofibrinogenemia can be inherited in either autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive patterns. Factor I (1) deficiency affects men and women equally.

Factor II (2) deficiency is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Both parents must carry the gene to pass the disorder on to their children. Factor II (2) deficiency affects men and women equally.

Factor V (5) deficiency is usually inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Both parents must carry the gene to pass the disorder on to their children. Factor V (5) deficiency affects men and women equally.

Factor VII (7) is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Both parents must carry the gene to pass the disorder on to their children. Factor VII (7) deficiency affects men and women equally.

If you want more information about factor VII (7) deficiency, please go to the Factor VII (7) Booklet.

Factor X (10) is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Both parents must carry the gene to pass the disorder on to their children. Factor X (10) deficiency affects men and women equally.

If you want more information about factor X (10) deficiency, please go to the Factor X (10) Booklet.

Factor XI (11) deficiency is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Both parents must carry the affected gene to pass the disorder on to their children. In some cases, factor XI (11) deficiency can also be inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.3 This means children with only one affected parent may inherit the condition. Men and women are affected by factor XI (11) deficiency equally.

Factor XII (12) deficiency is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Both parents must carry the gene to pass the disorder on to their children. Factor XII (12) deficiency affects men and women equally. It is more common in Asian people or Pacific Islander people.

Factor XIII (13) deficiency is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Both parents must carry the gene to pass the disorder on to their children. Factor XIII (13) deficiency affects men and women equally.

If you want more information about factor XIII (13) deficiency, please go to the Factor XIII (13) Booklet.

How Does a Person Get a Rare Platelet Disorder?

Rare platelet disorders can be inherited in different ways, depending on the disorder. Some disorders are inherited through an autosomal recessive pattern while others may be inherited through an autosomal dominant or X-linked pattern.

BSS is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern.2 Both parents must carry the abnormal gene to pass the disorder on to their children. BSS affects men and women equally.

GT is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Both parents must carry the abnormal gene to pass the disorder on to their children. GT affects men and women equally.

If you want more information about Glanzmann’s Thrombasthenia, please go to the Glanzmann’s Thrombasthenia Booklet.

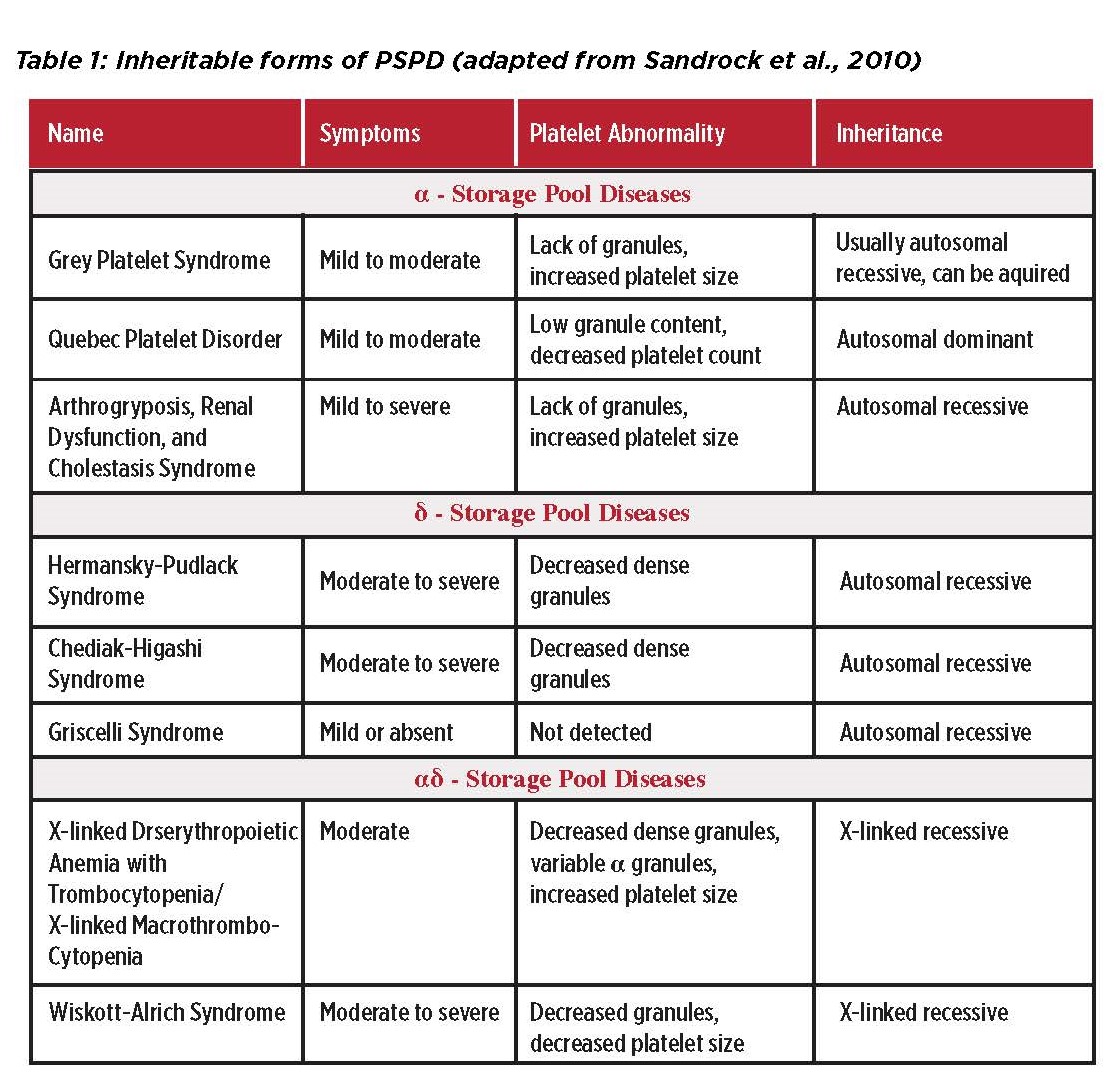

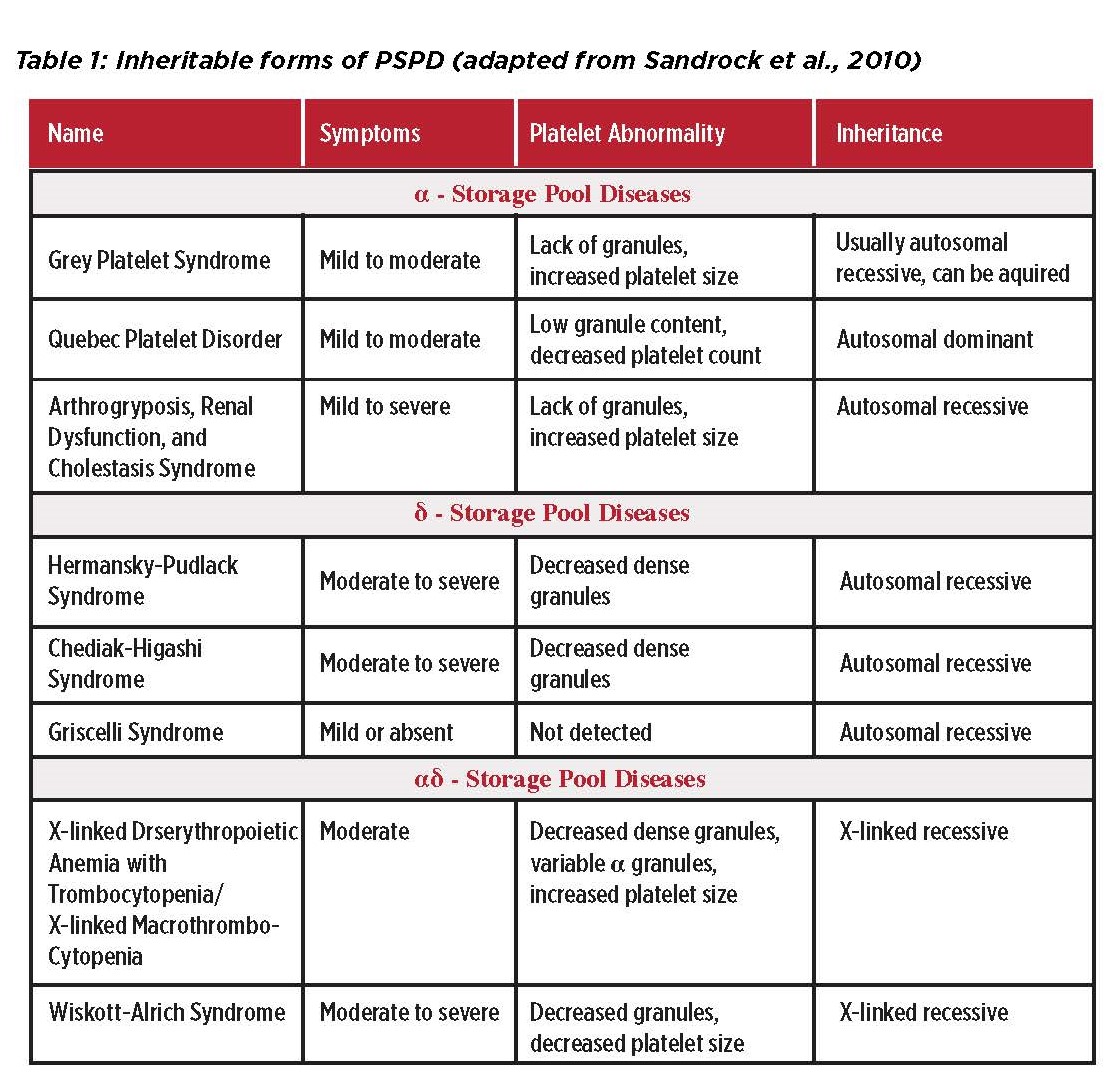

Forms of PSPD may be inherited in an autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked pattern. See the chart below for more detail on how the different forms of PSPD are inherited. If you want more information about Platelet Storage Pool Deficiency, please go to the Platelet Storage Pool Deficiency Booklet.

1. CDC. (2021, June 29). How von Willebrand disease is inherited. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/vwd/inherited.html

2. NORD. (2018, June 26). Bernard-Soulier syndrome. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/bernard-soulier-syndrome/#:~:text=Bernard%2DSoulier%20syndrome%20is%20usually,abnormal%20gene%20from%20each%20parent.

3. NORD. (2022, April 27). Factor XI deficiency. NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/factor-xi-deficiency/#:~:text=Factor%20XI%20deficiency%20is%20usually,working%20gene%20from%20each%20parent